Understanding Carbon Markets: Approaches and Experiences

Prantik Chakraborty

May 06, 2024

Carbon markets are the trading systems of carbon credits that allow companies and people to offset their greenhouse gas emissions by buying carbon credits from emission-reducing companies. The tradable ‘carbon credits’ can be generated by an organization through the reduction or removal of greenhouse gases from the atmosphere, such as switching from fossil fuel to renewable energies or increasing or conserving carbon stocks in ecosystems such as forests (World Bank, 2022). However, these tradable carbon credit certificates are issued by a registered authority (i.e., market regulator) strictly after verification of the claims. Several countries worldwide are exploring ways of pricing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions as a climate change mitigation tool (World Bank, 2022). The carbon market can provide incentives to the market to adopt low-cost options and attract technology and finance/funding toward sustainable projects that generate low GHG emissions.

Under the 1990 Clean Air Act modifications, emissions trading was first implemented in the United States to regulate air emissions of sulphur dioxide (SO2). Regulators and businesses recognised emissions trading’s flexibility and cost-effectiveness for environmental risk management, leading to its investigation for controlling other environmental issues such as NOX, CO2, and greenhouse gas emissions (Larson et al. 2003). Carbon markets are expected to be a vehicle for mobilizing a significant portion of investments required by economies to transition toward low-carbon pathways (BEE, 2022).

There are international, supranational, national and subnational functioning carbon markets in the world and more than 2/3 of countries across the globe have plans underway to use carbon markets to meet their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) to the Paris Agreement (World Bank, 2022).

Moreover, the leading initiatives of the Global North, i.e., the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), have been instrumental in conducing countries with export orientation to introduce and develop their domestic carbon markets (Zhong & Pei, 2023).

Approaches to Emissions Trading

Three different approaches of emission trading are usually adopted globally – (i) cap-and-trade, (ii) baseline-and-credit and (iii) offset.

Within cap-and-trade approach, regulatory bodies are responsible for implementing a predetermined limit on the overall amount of emissions allowed within a specific jurisdiction, commonly referred to as an emissions cap. The programme participants are granted credits by regulatory authorities, which are allocated based on the anticipated or permitted amount of pollution (measured in tonnes of pollutants per year) that they are authorised to release. These credits may be obtained through various means, such as direct allocation or acquisition via auction. If the participants surpass the predetermined limit, they are required to procure additional credits from fellow participants who have an excess supply of credits. This implies that the latter kind of participants have emitted less amount of pollutants than their allocated allowance which helps maintain a balance in the ecosystem. Therefore, the overall level of pollution is constrained by a predetermined limit, known as a cap. Through the mechanism of trading, the allocation of pollution becomes more efficient. Participants who can reduce emissions in a cost-effective manner will take action and reap the benefits of engaging in trade with those who are unable to do so (Allayannis & Tenguria, 2011).

In accordance with the baseline-and-credit approach, the regulatory body establishes an emissions output baseline for all entities responsible for pollution. Subsequently, a comparison is made between the projected emissions and the actual emissions. In the realm of environmental regulation, entities that release pollutants at a level lower than their established baseline are rewarded with credits, whereas those who surpass their baseline levels are obligated to procure credits. These credits have the potential to be exchanged in the market. Market-based instruments help setting the framework in this regard.

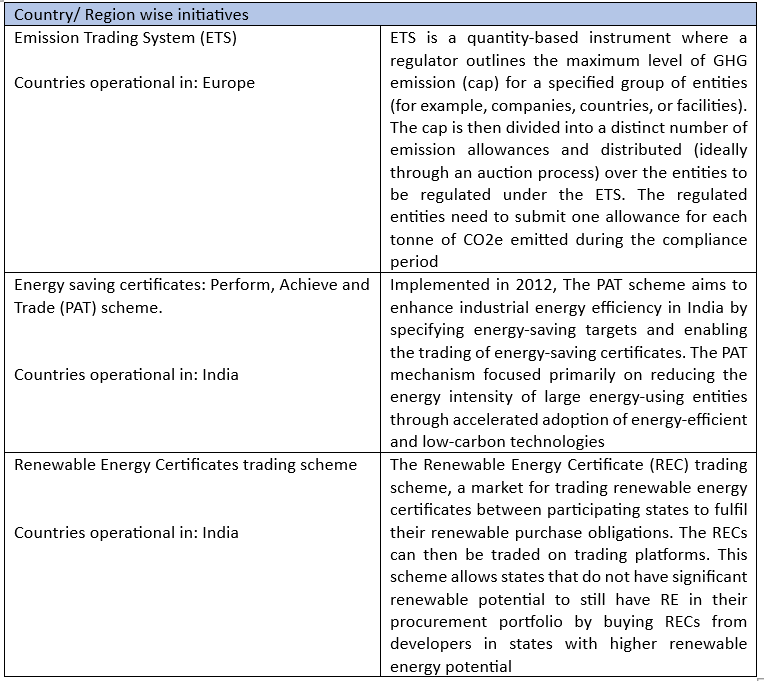

A brief overview of the international market-based instruments is provided in the table below (Allayannis & Tenguria, 2011).

Table1: Market based instruments (BEE, 2022) (Singh & Chaturvedi, 2023)

In the context of the baseline-and-credit system, it is important to note that the baseline level of emissions remains constant. This implies the existence of an implicit cap, which is equivalent to the total of the baseline emissions. On the contrary, the cap-and-trade system operates with an explicit aggregate cap. The allocation of credits is contingent upon the disparity between the anticipated and realised levels of emissions. In theory, it can be argued that cap-and-trade and baseline-and-credit systems are equivalent, provided that the implicit cap in the baseline-and-credit system remains fixed and matches the fixed cap in the cap-and-trade system. However, it is important to note that the implicit cap has the potential to fluctuate based on the overall level of aggregate output, thereby creating significant differences between the two approaches (Allayannis & Tenguria, 2011).

A carbon offset is a form of commodity that symbolises the reduction of one metric tonne of carbon-dioxide (CO2) equivalent achieved through a qualifying carbon-reduction project. The offset may or may not accurately reflect the tangible decrease in carbon dioxide emissions. In principle, an offset signifies an endeavour that serves to hinder or counterbalance (offset) the release of one metric tonne of tangible CO2 emissions. Some examples of offset projects encompass various initiatives such as renewable-power generation, energy efficiency projects, and forestry and industrial-waste remediation. In the realm of offsetting, it is imperative to acknowledge the existence of diverse governing bodies and certifications that diligently strive to guarantee the authenticity and accurate accountability of offsets (Allayannis & Tenguria, 2011). The following table discusses different market-based instruments which are in application for emission trading system.

Table 2: Region-based Markets (BEE, 2022)

Carbon markets across the globe

Early Initiatives: The European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) serves as a fundamental tool within the EU’s policy framework to address climate change and achieve the objective of minimising greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the most economically efficient manner possible. The system accounted for approximately 36% of the overall emissions generated within the European Economic Area (EEA) during the period of 2020-21. This encompassed a wide range of activities, including those from the power sector, manufacturing industry, and aviation, which includes flights originating from the EEA and destined for the United Kingdom (ICAP).

The European Union Emissions Trading Scheme (EU ETS), which was first implemented in 2005 and is currently in its fourth trading phase, holds the distinction of being the longest-standing operational system of its kind. Since the year 2005, there has been a significant reduction in emissions by stationary installations, amounting to approximately 43% of the baseline (1990 Emission level) (ICAP).

Since its inception, the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) has undergone a series of comprehensive reforms aimed at enhancing its effectiveness and efficiency. The most recent iteration of the system’s framework was finalised in 2018 and was implemented in January 2021, specifically for Phase 4. In 2021, the European Commission put forth additional reforms to the ETS with the aim of fulfilling the objectives outlined in the “European Green Deal” (ICAP).

As of 2020, a linkage has been established between the European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) and the Swiss Emissions Trading System (Swiss ETS). In order to ensure compliance with the linking arrangement, it is imperative to duly take into account any policy updates in either jurisdiction. Besides the EU emissions trading system, which are the most popular and widely known, national or sub-national systems are operating or under development in Canada, China, Japan, New Zealand, South Korea, and Switzerland (Singh & Chaturvedi, 2023). The US led Energy Transitions accelerator (ETA) was established with the aim to stimulate demand for carbon credits in developing countries at national and subnational levels.

Developing Markets: Under Article 6 of the Paris agreement, some more initiatives on carbon trading were taken after negotiations at COP 27. With UNDP’s support, Switzerland, Ghana, and Vanuatu entered voluntary cooperation for carbon markets to boost climate action through sustainable farming practises. An African Carbon Markets Initiative has also been established aiming at scaling up carbon credit revenues for African countries. Jordan has also developed frameworks for carbon credits in exchange for capital flows for climate mitigation, whose system is being replicated in the West Bank region, Gaza and Sri Lanka (World Bank, 2022).

India’s Upcoming Carbon Market

The Government of India has passed an amendment to the Energy Conservation Act, 2001, which lays the foundation for the establishment of a domestic carbon market in India, providing legal framework for the same with the objective of decarbonizing the Indian economy across multiple sectors by pricing the Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions through trading of the Carbon Credit Certificates. In this regard, the Bureau of Energy Efficiency (BEE), which lies under the central government has brought out a draft blueprint on Indian Carbon Markets (ICMs), targeting high carbon emitting sectors such as energy, steel and cement (BEE, 2022). The development of such a market will mobilize new mitigation opportunities through demand for emission credits by private and public entities and is expected to contribute to achieving India’s updated nationally determined contributions (NDC)[1](CER, 2023). Bureau of Energy Efficiency, Ministry of Power, along with Ministry of Environment, Forest & Climate Change are developing the Carbon Credit Trading Scheme for this purpose (BEE, 2022).

The government is looking to encash the carbon markets in supporting its goals across various time horizons. While India has Carbon benefit market mechanisms in place, they are yet to realize their full potential and thus, is unable to provide the required support for decarbonisation of the Indian energy sector and industries. To create an efficient and effective domestic carbon market mechanism in India and reach a viable scale of operations, it was therefore deemed necessary to set up a single carbon market mechanism, integrating the existing PAT and REC markets into it (BEE, 2022). A single market at the national level, as opposed to having multiple sectoral market instruments, is expected to reduce transaction costs, improve liquidity, enhance a common understanding and targeted capacity development, and streamline the accounting and verification procedures. This carbon market mechanism will set targets for the mandated participants, as per existing and emerging policy objectives, and their achievement will count towards India’s NDCs (CER, 2023; Singh & Chaturvedi, 2023).

The proposed domestic market mechanism by BEE is distinct from the corresponding international carbon market arrangements under Article 6 of the Paris agreement and cannot substitute for the international markets for trading on the Article 6 market mechanisms. Neither can they be declared as “equivalent” under any provision of the Paris Agreement. It follows that while carbon credits for trading in the Indian Carbon Market would be issued under domestic arrangements, those for international trading under Article 6 would need to be issued as per the international protocols (BEE, 2022).

It is proposed that under the Indian Carbon Market, there will be two mechanisms, viz., a carbon credit trading mechanism for the obligated sectors and a project-based offset scheme for non-obligated and non-energy sectors (BEE, 2022).

Phase 1 Offset Market: This phase proposes to open the Indian voluntary markets to voluntary buyers in addition to the existing consumers by increasing demand in the voluntary carbon market (short term). In this, the fungibility of energy-saving certificates and RECs will be worked on and traded as carbon offsets.

Phase 2 Compliance Market: Under this phase, the obligated entities monitor, report, and verify their GHG emissions and performance to demonstrate compliance and will have to meet their obligation by trading the in-carbon credit certificates and the credits generated/traded in the compliance market. It aims to enable the complete transition of the current energy efficiency compliance market under the PAT scheme to the Carbon emissions compliance market (BEE, 2022; Singh & Chaturvedi, 2023).

In addition, the Indian Carbon Market will develop methodologies for the estimation of carbon emissions reductions and removals from various registered projects and stipulate the required validation, registration, verification, and issuance processes to operationalize the scheme. Monitoring, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) guidelines for the emissions scheme will also be developed after consultation. A comprehensive institutional and governance structure will be set up with specific roles for each party involved in the execution of the Indian Carbon Market. Capacity building of all entities will be undertaken for up-skilling in the subject matter (BEE, 2022). Key stakeholders, including Accredited Energy Auditors, Carbon/Energy Verifiers, Sector Experts, etc, were consulted for the same while developing the structure for the Indian Carbon Market during the policy draft proposal (Singh & Chaturvedi, 2023).

[1] India’s NDCs include targets such as reducing emission intensity of GDP by 45% by 2030, from the 2005 levels, to achieve about 50 percent cumulative electric power installed capacity from non-fossil fuel-based energy resources by 2030, creating a 2.5-3 billion carbon sink through forest cover by 2030 to name a few (BEE, 2022).